Actually, I have lots of astronomers I admire but I’m going to talk about one who interests truly mirror my own, Sir William Herschel.

Born Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel on November 15, 1738, in Hanover, Germany, Herschel was immersed in music from an early age. His father, Isaak Herschel, an oboist in the Hanover Military Band, instilled in him a profound appreciation for the art. Demonstrating prodigious talent, young William mastered multiple instruments. Herschel was a contemporary of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven—he embarked on a musical career that saw him composing and performing across Europe.

In 1757, amidst the turmoil of the Seven Years’ War, Herschel relocated to England, seeking refuge and new opportunities. There, he initially sustained himself by copying music and offering private lessons. His exceptional skills did not go unnoticed; by 1766, he secured the prestigious position of organist at the Octagon Chapel in Bath, a city celebrated for its cultural and musical vibrancy. Beyond his organist duties, Herschel became the Director of Public Concerts, where he frequently showcased his compositions. His oeuvre includes 24 symphonies, numerous concertos for oboe, violin, viola, and organ, as well as various chamber and sacred works. Notably, his Symphony No. 14 in D major, composed in 1762, exemplifies his adeptness in orchestral writing.

From Harmonies to Heavens: The Astronomical Awakening

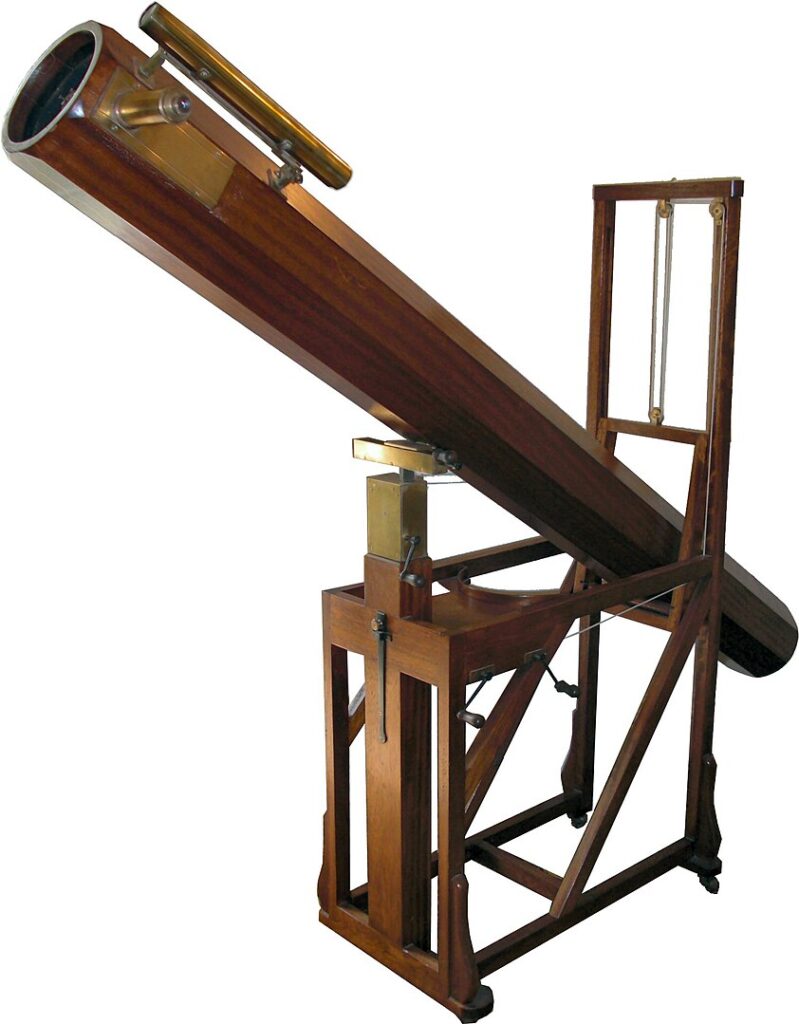

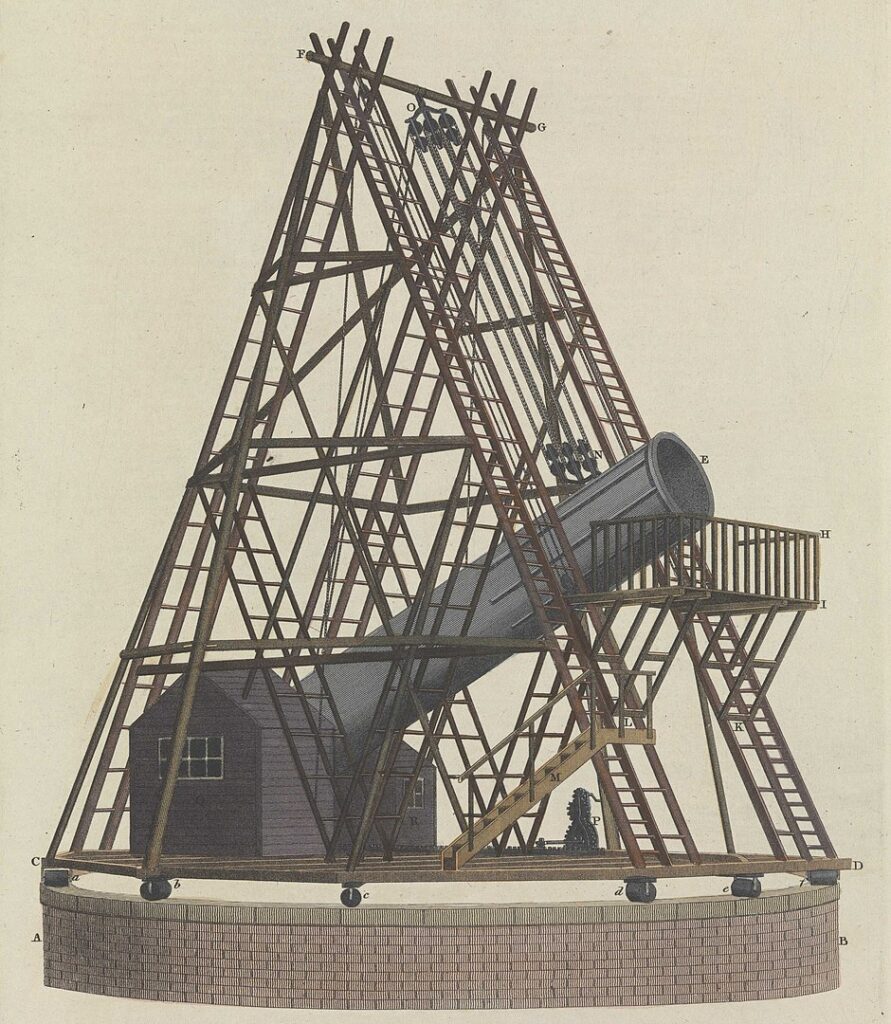

While music was his livelihood, the mysteries of the cosmos beckoned Herschel with an irresistible allure. His interest in the mathematical aspects of music led him to delve into works on harmonics and optics. This academic pursuit sparked his fascination with telescope construction and celestial observation. By 1773, he had begun building his own telescopes and conducting nightly observations.

The pinnacle of Herschel’s astronomical career came on March 13, 1781, when he identified a new celestial object. Initially believing it to be a comet, further observations revealed it as a new planet, which he called “Georgian star” (Georgium sidus), but was later named Uranus. This groundbreaking discovery expanded the known boundaries of the solar system and earned Herschel international acclaim. In recognition, King George III appointed him as the King’s Astronomer, providing him the means to abandon his musical career and devote himself entirely to astronomy.

In 1787, he discovered two of Uranus’s moons, Titania and Oberon, further expanding our understanding of planetary systems. His keen observations also led to the identification of two additional moons of Saturn, Mimas and Enceladus, in 1789. These discoveries were monumental, as they unveiled celestial bodies previously unknown to humanity.

Charting the Cosmos: Stellar Contributions

Herschel’s curiosity wasn’t confined to our solar system. He conducted extensive surveys of the night sky, cataloging over 2,500 nebulae and star clusters. His meticulous work culminated in the “Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars,” which remained a cornerstone reference for astronomers. Through his studies of double stars, Herschel provided empirical evidence that many such pairs are gravitationally bound, offering early insights into stellar dynamics.

In a groundbreaking experiment in 1800, Herschel discovered infrared radiation. By passing sunlight through a prism and measuring the temperature just beyond the visible red spectrum, he detected a form of light invisible to the human eye but perceptible as heat. This revelation expanded the known electromagnetic spectrum and opened new avenues in the study of light and energy.

A Sibling Partnership: Caroline Herschel

Central to his success was his sister, Caroline Herschel, whose own remarkable contributions have earned her a distinguished place in the annals of science. Caroline’s journey into astronomy began as an assistant to her brother, but she soon emerged as a formidable astronomer in her own right. Between 1786 and 1797, she discovered eight comets, with her first, Comet C/1786 P1, identified on August 1, 1786. This achievement marked the first recorded discovery of a comet by a woman. Her diligent sweeps of the sky also led to the identification of 14 new nebulae and the independent discovery of Messier 110, a companion galaxy to the Andromeda Galaxy.

Legacy: An Enduring Harmony

Today, Herschel’s dual legacy endures. His musical compositions, though overshadowed by his astronomical achievements, offer insight into the rich musical landscape of 18th-century England. Recordings of his symphonies and concertos have been revived, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his artistic prowess. Simultaneously, his astronomical discoveries laid the foundation for modern observational astronomy, inspiring generations of stargazers to look beyond the known and explore the vastness of the universe.

Personally inspiring, William Herschel’s life exemplifies the harmonious fusion of art and science, illustrating how diverse passions can converge to yield extraordinary contributions to human knowledge and culture.